Hi there, I am so excited to finally share with you, that I was invited by Lund Humphries to make a review with my impressions on their two new titles of amazing book series Illuminating Women Artists, one about Eufrasia Burlamacchi and the other about Clara Peeters. Few months ago, I invited wonderful Erika Gaffney, from Lund Humphries to write an article about this collection, that you can read it here.

This collection is an incredible opportunity to make the history and the work of some great artists of the past that are, still today, unknown for a great part of the public. Both books bring the history of the artists’ lifes and the context they lived in, which is essential to have a better understanding of their works. Not only this, but these books make academic knowledge of the artists more accessible.

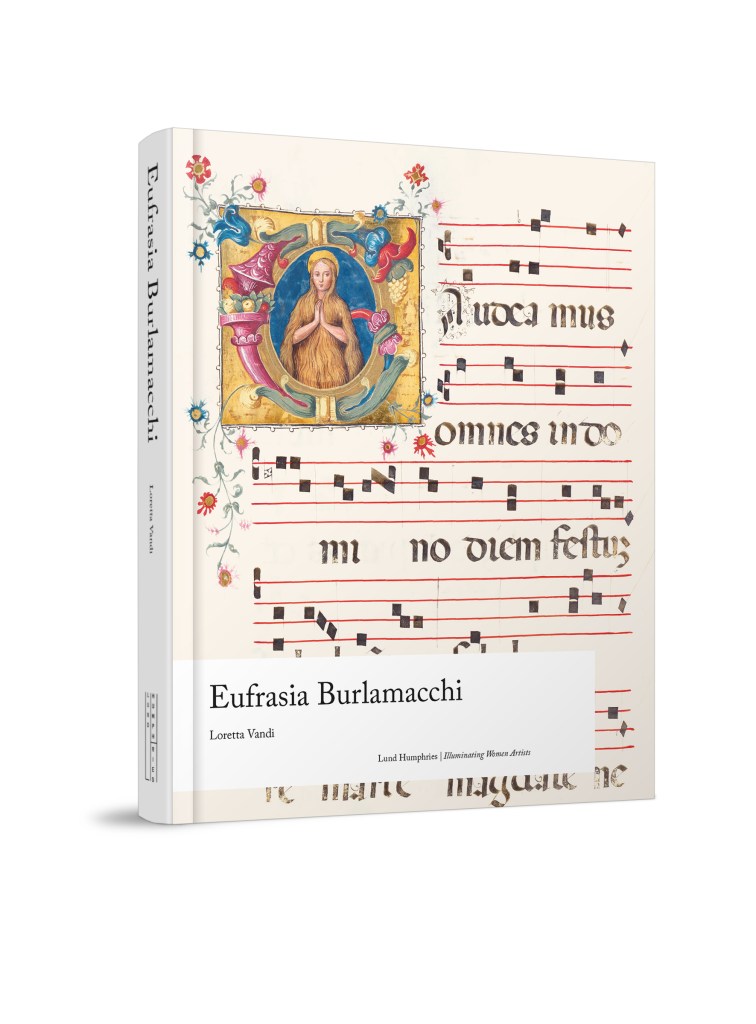

Eufrasia Burlamacchi

The first one, about Eufrasia Burlamacchi, is written by Loretta Vandi, who is an Art History professor at Scuola del Libro in Urbino, Italy. I must confess that I haven’t heard anything about Eufrasia before the reading of this book, and I get completed fascinated about her talent. She was a Dominican sister who practised the illumination of manuscripts during the first quarter of 16th century in Lucca, Italy. Unfortunately, it doesn’t exist an artistic biography of her, probably due the lack of documents about her and for the art she practised.

Burlamacchi was a very talented early modern artist, who was based in the Observant convent of San Domenico, a convent that followed the Savonarolan reform, and for this reason it was a very strict enclosure environment. This is a very important detail to understand her art, since during her artistic development she had neither encounters nor meetings, neither travels nor direct experiences with the artistic world of her time. According to Vandi “she was one of the interpreters of a spiritual reform that found in illumination an outlet for manifesting values”.

Conventual environments were entirely different realities, though they were very secluded places, they’re not secluded enough to impede circulation of some ideas and artworks that provoked reactions from the nuns in both the religious and artistic fields. Also, craftwork was an important part of the nun’s communal life. Evidence from the mid-16th century was found of paintings and sculptures being produced in convents to be sold or given as gifts.

The Savonarolan reform prescribed the nuns various sorts of renunciation, such as food, personal and communal property, and artistic activity, with the aim of promoting spiritual self-determination. In relation to artistic activity, what was censured by Savonarolan reform was the large-scale and lucrative production, such as we could see in some convents with the embroidery or music.

Even if she did not receive a proper artistic education, illumination was a freer type of art, there was no need to study anatomy, or natural light, unlike painting. She limited her inventiveness to the ornamental apparatuses, never changing the traditional 15th century iconography derived from the Sacred Scripture. Something that I found truly curious, it’s that even if she never experienced mystic visions, she could give form in texts that resonated with them.

It is also important to note that her talent was appreciated at her time, but all the information we have concerning her career belongs to the conventual records, destined to remain within a limited and self-referential history. Burlamacchi wrote, noted and illuminated eight manuscripts, and not only for her own convent, San Domenico, she illuminated one Antiphonary for the San Martino Cathedral, and a two-volume Gradual for the San Romano monastery. For San Domenico, she illuminated four Antiphonaries, and one Gradual.

Her proficiency led her to instruct some of the younger sisters of her convent in order to establish a workshop at the convent, especially because the 16th century was a moment of flourishment for illumination in relation to the diffusion of illustrated books, including within female religious houses. The workshop founded by her operated until the 19th century. Burlamacchi was not only proficient in the illumination of manuscripts she was also an accomplished singer.

She acquired significance as a historic figure. According to Vandi, in historical terms, there are extensive records about Eufrasia Burlamacchi, both direct and indirect, and that would be enough to write an individual history of her.

One of my favourite parts of the book was to discover that Eufrasia Burlamacchi had probably created an emblem for herself, as she never signed, she found a different way to show her presence by using two cherries hanging from acanthus leaves, these cherries were not integrated to the rest of the work.

Clara Peeters

Clara Peeters was not a complete stranger to me, I went to her solo exhibition The Art of Clara Peeters at the Museo del Prado in Madrid years ago, this was the first solo exhibition that the Prado dedicated to a woman artist. The book is written by Alejandro Vergara, who is the curator responsible for the Flemish collection of the Museo del Prado, and the curator of her solo exhibition. Clara Peeters has not been the focus of much scholarly attention until now, as most of women artists of modern era. The book is a truly immersion on Peters’s artistry, and in the Antwerp of her time. Through it Vergara makes comparisons of her works and those of other artists of the time, especially those based in Antwerp, what helps to understand her context. Once we immerge in her visual language, we can understand how she transformed the reality of her daily life into art. But not only this, what we see is also the reflection of the culture of that time.

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

There is not much information about her life. What we know for sure is that she based her practice in Antwerp, which was from the beginning of the 16th century one of the main artistic centres of Europe. We also know that her first painted signed is from 1607. According to Vergara, the problem with identifying Peeters in Antwerp is that her name is not listed in the records of the painter’s guild. The regulations of the time did not specifically forbid the practice to women, and in later 16th and early 17th centuries, there are many persons in Antwerp with “Peeters” as last name, including several painters. One of them is Henrick Peeters, it is known that he married to a woman named Clara Lamberts in Antwerp in 1605. Even though there are no documents specifying that this Clara was a painter, there is enough circumstantial evidence to make a strong case for therefore, our Clara. Being married to a painter would explain her exemption from registering with the city’s guild.

County Museum of Art, CA

She was part of the second Antwerp boom, among cosmopolitan artists such as Rubens and Jacob Jordaens. The ambition and cosmopolitan outlook were defining characteristics of Antwerp’s artists, and we can see it in Peeters’ career and art. In her work she displayed objects associated with the traditional social habits, and elitist activities such as hunting and collecting object that proclaimed distinction. She seems to have been less well connected than some of her contemporaries. Through her realistic art we can note an entrepreneurial mentality.

By that time women were considered inferior to men, physically and intellectually, however there were some activities permitted and which included going outdoors, especially when they complimented those of the husband. It remains likely that her singular speciality in still lifes was part as a consequence of the restrictions of gender, even if portraiture was also a viable speciality for women.

Probably the most interesting feature of her work and the most commented too are her self-portraits. Their revelatory nature suggests a social tension. They are nearly hidden by their size and by their reflective nature, what makes them seem to be made by someone who is hiding but, at the same time, wishing to be seem. According to Vergara it is maybe a metaphor, it is the way she found to react to the limitations imposed by the society she lived in. Peeters was a discreet woman, what she may have considered as a necessity in a professional field dominated by men. But she was also a pioneer who wanted to be acknowledged. She knew about important precedents of these type of portraits, however painted reflections are more commons in art than reflected self-portraits. Even when we consider paintings made after her time, reflected self-portraits remain rare.

According to Alejandro Vergara, she can be further understood as a painter by the materials she used and her working methods. She used expansive materials (such as shell gold and lapis lazuli), and most of the materials conservators have detected in her works were considered standard in Antwerp. Apparently, she did not produce exact copies of her paintings. There are some paintings that her quality reveals or suggests they were painted by assistants who must have worked with her. Early documents suggest that she had some name recognition in the Northern Netherlands in the first decade of her artistic production.

My rate

For me both are 10/10!

I think that this collection is truly treasure for those who wants to get to know more about the life and career of women artists, especially by those such as Eufrasia Burlamacchi or Clara Peeters of whom we have so little information, since they haven’t received much attention from scholars and art historians.

Even if they had very different lifes, faced very different problems and challenges, there is something in their lives that is the same, something that is very evident at the same time that is very discreet, and which is present in the artistic world of many other women artists: the wish to be known. This desire to be recognised by their work, by their talent, we can see in Eufrasia’s cherries and in Clara’s reflected self-portraits. A little detail in their works, something that could even go unnoticed by those who see their works, but there they are, present in the invisible, hidden in the shadows, casting a small glow.

Curiosities:

- Girolamo Savonarola was known for his advocacy of the destruction of secular art and culture, and for his calls for Christian renewal. He denounced clerical corruption, despotic rule, and the exploitation of the poor.

- Eufrasia Burlamacchi lived between two reforms of Catholicism: Savonarolan and Lutheran. While she embraced Savonarolan, some of her relatives embraced Lutheran.

- The painting Woman seated at a table with precious objects is a very curious case. Even if it seems likely to be painted by Clara Peeters, according to Vergara, it is impossible to ascertain until the painting I better studied and known. This painting belongs to a private collection.

- One of the reasons to believe that Clara Peeters was based in Antwerp is the constant presence in her paintings of a silver knife with a maker’s mark from this city.

- The garland painted by Clara Peeters is one of the two painting made by her that include human figures, other than her self-portraits in reflection.

References:

- Vergara-Sharp, Alejandro. Illuminating Women Artists: Renaissance and Baroque, Clara Peeters. 2025.

- Vandi, Loretta. Illuminating Women Artists: Renaissance and Baroque, Eufrasia Burlamacchi. 2025.

- Images: Lund Humphries and Museo Nacional del Prado.

Discover more from Women'n Art

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.